Introduction

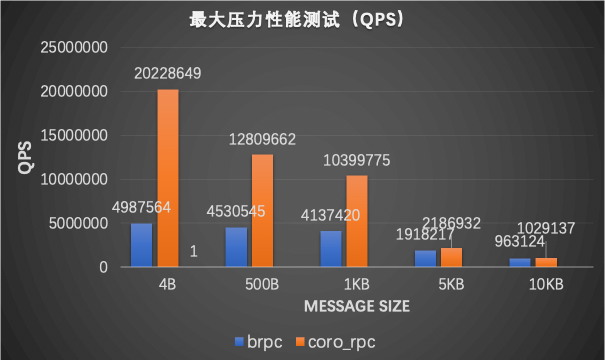

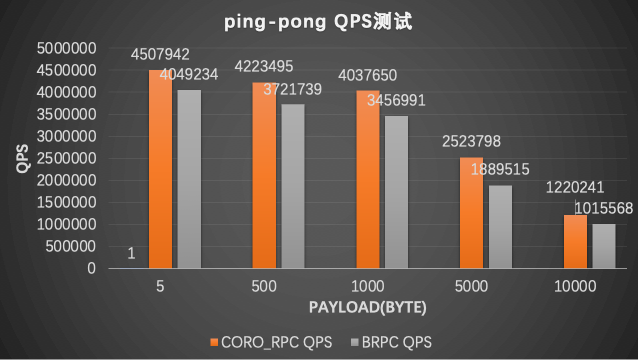

coro_rpc is a high-performance Remote Procedure Call (RPC) framework in C++20, based on stackless coroutine and compile-time reflection. In an echo benchmark test on localhost with 96-cores cpu, it reaches a peak QPS of 20 million (in pipeline) or 4.5 million(2000 connection in ping-pong), which exceeds other RPC libraries, such as grpc and brpc. Rather than high performance, the most key feature of coro_rpc is easy to use: as a header-only library, it does not need to be compiled or installed separately. It allows building an RPC client and server with a few lines of C++ code.

The core design goal of coro_rpc is usability. Instead of exposing too many troublesome details of the underlying RPC framework, coro_rpc provides a simplifying abstraction that allows programmers to concentrate principally on business logic and implement an RPC service without much effort. Given such simplicity, coro_rpc goes back to the essence of RPC: a remote function call similar to a normal function call except for the underlying network I/O. So coro_rpc user does not need to care about the underlying networking, data serialization, and so on but focus on up-layer implementations. And coro_rpc provides simple and straightforward APIs to users. Let's see one simple demo below

Usability

server

- define the RPC function

// rpc_service.hpp

inline std::string echo(std::string str) { return str; }- regist the RPC function and start the server

#include "rpc_service.hpp"

#include <ylt/coro_rpc/coro_rpc_server.hpp>

int main() {

coro_rpc_server server(/*thread_num =*/10, /*port =*/9000);

server.register_handler<echo>(); // register rpc function

server.start(); // start the server and blocking wait

}Basically one could build a RPC server in 5~6 lines by defining the rpc function and starting the server, without too much details to be worried about. Now let see how a RPC client works.

An RPC client has to connect to the server and then call the remote method.

#include "rpc_service.hpp"

#include <ylt/coro_rpc/coro_rpc_client.hpp>

Lazy<void> test_client() {

coro_rpc_client client;

co_await client.connect("localhost", /*port =*/"9000");

auto r = co_await client.call<echo>("hello coro_rpc"); // call the method with parameters

std::cout << r.result.value() << "\n"; //will print "hello coro_rpc"

}

int main() {

syncAwait(test_client());

}As demonstrated above, it is also very convenient to build a client. There's not much difference between an RPC function call with a local function one: simply provides the function name and parameters.

The server/client implementation shows the usability and core features of coro_rpc. Also, it shows us the core concept of RPC: that users can invoke remote methods in a way with local functions, and users will focus their efforts on RPC functions.

Another usability of coro_rpc is that: there are barely any constraints on the RPC function itself. One could define an RPC function with any number of parameters. The parameters' type should be legal for struct_pack. (See struct pack type system). The serialization/deserialization procedures are transparent to users and the RPC framework will take care of them automatically.

RPC with any parameters

// rpc_service.h

// client needs to include this header and the implementation details are hidden

void hello(){};

int get_value(int a, int b){return a + b;}

struct person {

int id;

std::string name;

int age;

};

person get_person(person p, int id);

struct dummy {

std::string echo(std::string str) { return str; }

};

// rpc_service.cpp

#include "rpc_service.h"

int get_value(int a, int b){return a + b;}

person get_person(person p, int id) {

p.id = id;

return p;

}And in server, we define the following:

#include "rpc_service.h"

#include <ylt/coro_rpc/coro_rpc_server.hpp>

int main() {

coro_rpc_server server(/*thread_num =*/10, /*port =*/9000);

server.register_handler<hello, get_value, get_person>();//register the RPC functions of any signature

dummy d{};

server.register_handler<&dummy::echo>(&d); //register the member functions

server.start(); // start the server

}In client, we have the following:

# include "rpc_service.h"

# include <coro_rpc/coro_rpc_client.hpp>

Lazy<void> test_client() {

coro_rpc_client client;

co_await client.connect("localhost", /*port =*/"9000");

//RPC invokes

co_await client.call<hello>();

co_await client.call<get_value>(1, 2);

person p{};

co_await client.call<get_person>(p, /*id =*/1);

auto r = co_await client.call<&dummy::echo>("hello coro_rpc");

std::cout << r.result.value() << "\n"; //will print "hello coro_rpc"

}

int main() {

syncAwait(test_client());

}The input parameter and return type of get_person is a struct. The serialization/deserialization are automatically done by library struct_pack with compile-time reflection. Users are not required to take efforts on such procedures.

Compare with grpc/brpc

Usability

| RPC | Define DSL | support coroutine | code lines of hello world | external dependency | header-only |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| grpc | Yes | No | 70+ helloworld | 16 | No |

| brpc | Yes | No | 40+ helloworld | 6 | No |

| coro_rpc | No | Yes | 9 | 3 | Yes |

Asynchronous Model

Asynchronous callback VS. coroutine

- grpc asynchronous client

//<https://github.com/grpc/grpc/blob/master/examples/cpp/helloworld/greeter_callback_client.cc>

std::string SayHello(const std::string& user) {

// Data we are sending to the server.

HelloRequest request;

request.set_name(user);

// Container for the data we expect from the server.

HelloReply reply;

// Context for the client. It could be used to convey extra information to

// the server and/or tweak certain RPC behaviors.

ClientContext context;

// The actual RPC.

std::mutex mu;

std::condition_variable cv;

bool done = false;

Status status;

stub_->async()->SayHello(&context, &request, &reply,

[&mu, &cv, &done, &status](Status s) {

status = std::move(s);

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(mu);

done = true;

cv.notify_one();

});

std::unique_lock<std::mutex> lock(mu);

while (!done) {

cv.wait(lock);

}

// Act upon its status.

if (status.ok()) {

return reply.message();

} else {

std::cout << status.error_code() << ": " << status.error_message()

<< std::endl;

return "RPC failed";

}

}- brpc asynchronous client

// <https://github.com/apache/incubator-brpc/blob/master/example/asynchronous_echo_c%2B%2B/client.cpp>

void HandleEchoResponse(

brpc::Controller*cntl,

example::EchoResponse* response) {

// std::unique_ptr makes sure cntl/response will be deleted before returning.

std::unique_ptr<brpc::Controller> cntl_guard(cntl);

std::unique_ptr<example::EchoResponse> response_guard(response);

if (cntl->Failed()) {

LOG(WARNING) << "Fail to send EchoRequest, " << cntl->ErrorText();

return;

}

LOG(INFO) << "Received response from " << cntl->remote_side()

<< ": " << response->message() << " (attached="

<< cntl->response_attachment() << ")"

<< " latency=" << cntl->latency_us() << "us";

}

int main() {

example::EchoService_Stub stub(&channel);

// Send a request and wait for the response every 1 second.

int log_id = 0;

while (!brpc::IsAskedToQuit()) {

// Since we are sending asynchronous RPC (`done' is not NULL),

// these objects MUST remain valid until `done' is called.

// As a result, we allocate these objects on heap

example::EchoResponse* response = new example::EchoResponse();

brpc::Controller* cntl = new brpc::Controller();

// Notice that you don't have to new request, which can be modified

// or destroyed just after stub.Echo is called.

example::EchoRequest request;

request.set_message("hello world");

cntl->set_log_id(log_id ++); // set by user

if (FLAGS_send_attachment) {

// Set attachment which is wired to network directly instead of

// being serialized into protobuf messages.

cntl->request_attachment().append("foo");

}

// We use protobuf utility `NewCallback' to create a closure object

// that will call our callback `HandleEchoResponse'. This closure

// will automatically delete itself after being called once

google::protobuf::Closure* done = brpc::NewCallback(

&HandleEchoResponse, cntl, response);

stub.Echo(cntl, &request, response, done);

// This is an asynchronous RPC, so we can only fetch the result

// inside the callback

sleep(1);

}

}- coro_rpc client with coroutine

# include <coro_rpc/coro_rpc_client.hpp>

Lazy<void> say_hello() {

coro_rpc_client client;

co_await client.connect("localhost", /*port =*/"9000");

while (true){

auto r = co_await client.call<echo>("hello coro_rpc");

assert(r.result.value() == "hello coro_rpc");

}

}One core feature of coro_rpc is stackless coroutine where users could write asynchronous code in a synchronous manner, which is more simple and easy to understand.

Benchmark

System Configuration

Processor:Intel(R) Xeon(R) Platinum 8163 CPU @2.50GHz 96Cores

OS: Linux version 4.9.151-015.ali3000.alios7.x86_64

Compiler:Alibaba Clang13 C++20

Test case

Both the client and server are on the same machine, sending requests using different amounts of connections to do echo tests.

Peak QPS test

- Send data and receive data through a pipeline, put CPU under full load and get the highest qps

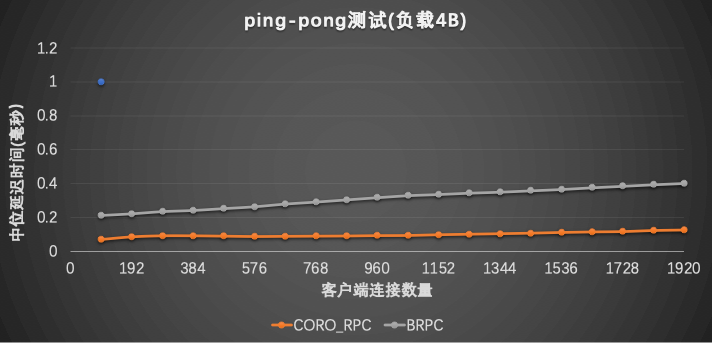

ping-pong test

- send the next request after the previous one is completed

- check the QPS as the number of connections increases.

- get the average latency of ping-pong

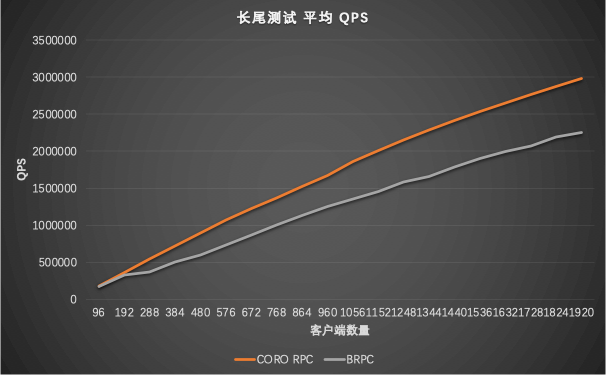

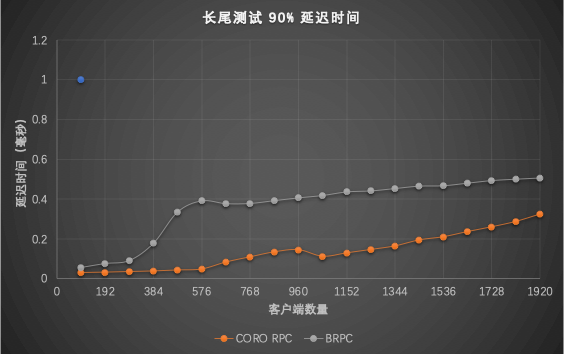

long-tail test

Notes on benchmark test

- grpc's QPS does not exceed 100,000, so it is not included in this benchmarking.

- The client is a coro_rpc based client for both coro_rpc and brpc stress test. It has better stress test performance compared to a brpc client(With a brpc client, the brpc client will drop 50%).

- brpc uses connection multiplexing, The actual number of socket connections is not that high(96)

Known Limitations

- Only little-endian is supported for now. Big-endian is working in progress

- Only C++ is supported and could not work across languages now, will support other languages later; Compiler should support C++20(clang13, gcc10.2, msvc2022)

- If any compile issue with

gcc -O3, please try option-fno-tree-slp-vectorize